Get ready to have a barrel of fun as we dive into the world of AR15 barrels! These babies have got it all – length, different profiles, gas systems, rifling, and twist rates. They’re like the rockstars of the firearm world, turning an ordinary rifle into a precision powerhouse! So buckle up and get ready to unlock the secrets of these Freedom-Seed-Delivery-Tubes. Let’s shoot for the stars!

Table of contents

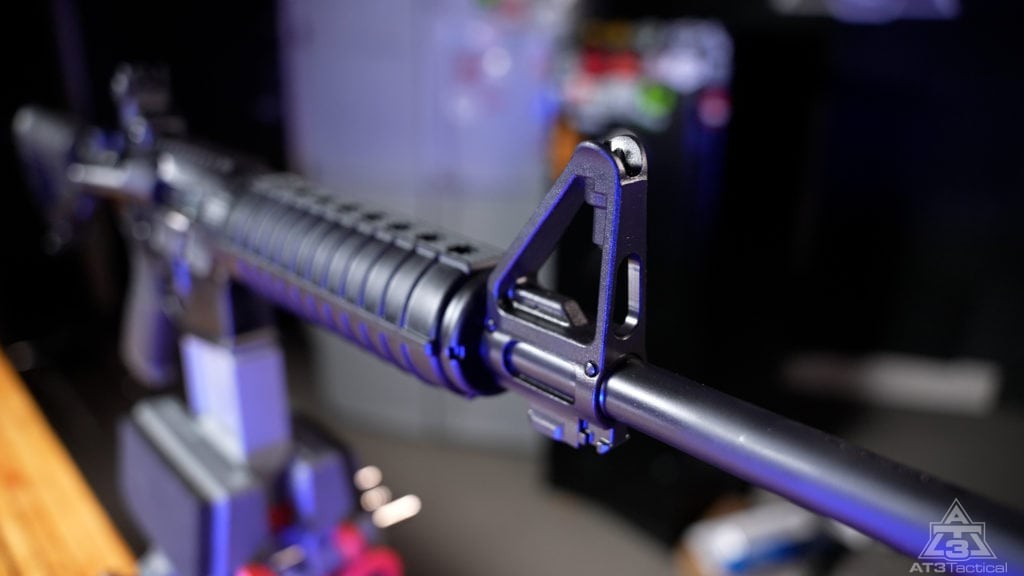

Is a Longer AR Barrel Length More Accurate?

To a lot of people, it’s simple: A longer barrel shoots more accurately than a short one. “It just shoots straighter,” they’d say, and they’d be right about that. But they’d be wrong, too.

The M16 rifle was built with a lightweight 20-inch barrel, which met military standards for accuracy. The newer M4 was shortened to make handling easier, with a 14.5″ barrel standard in the military version. While a 20-inch M16 barrel does shoot straighter than a 14.5″ or 16″ barrel, the shorter barrels are just as accurate.

You might notice a careful choice of words there. The longer barrel keeps the gases trapped behind the bullet longer so that when it leaves the muzzle, it comes with a higher velocity — usually somewhere around 3200 feet per second, depending on bullet weight, powder charge, barrel wear, etc.

It’s estimated that each inch of barrel lost will cost 25-50 fps in velocity, so you can expect around 3000-3100 fps from a 16″ barrel, and about 2900-3000 from a 14.5″ (tests with XM193 ammo chronographed about 78 deg F; actual velocities vary with load, atmospheric pressure, temperature, and barrel condition.

Either way, a bullet traveling slower will show a greater drop at a given range, and will have measurably less kinetic energy at all ranges — but the shorter barrel can still be consistent, and consistency, not velocity, is the key to accuracy. So if all you want is accuracy, you don’t need to choose a 24″ barrel — but if you want long range, the longer your barrel is, the better.

For distances too long for an M4 but not quite requiring a true sniper rifle, two longer-range rifles were developed: The DMR, or Designated Marksman’s Rifle, and the Special Purpose Rifle (SPR).

The DMR, with a 20″ barrel and special scope, was issued to selected riflemen within an infantry unit, who had been trained to engage the enemy at longer ranges. The SPR, with an 18″ barrel, is a light sniper rifle. It was again given a special scope, as well as a suppressor, and added to the weapons available to sniper-trained special forces personnel. Both the SPR and DMR are considered to be usable to ranges of 600 meters or more – well beyond the 440 meters that Colt told us the M16 could shoot.)

The vast majority of AR barrels fall between the 14.5″ military M4 type and the 20″ M16 size, with 16″ being currently the excepted standard for civilians. You can buy 14.5″ barrels, but for most of us, it would require a muzzle device at least 1.5 inches long, and permanently attached, to meet the legal 16″ minimum. Of course, if you put a muzzle device on a 16″ barrel, you get something a little over 17 inches long.

If you want barrels longer than 20″, it’s not too hard to find them in 22″ or 24″ lengths; generally, anything longer than that would be for target shooting and would have to be custom ordered.

If you want barrels shorter than 14.5″ (+ 1.5″!), there are two ways to do it legally (in some places): The SBR and the AR pistol!

Short Barreled AR-15’s and AR-15 Pistols

SBRs or short-barreled rifles have become more and more popular in the past few decades because of pop culture and a new wave of gun owners looking to the AR-style firearm for their home defense gun. These weapons often sport barrels in the 10-14″ range and are great for maneuverability, balance, and weight reduction. The downside is they also lose a lot of muzzle velocity, the operation can be harsh, reliability is compromised, and they can be harder to shoot.

In some areas, they’re simply illegal for civilians to own. Where they are legal, they require NFA processing with the accompanying $200 tax stamp.

A rifle is subject to the NFA only if the rifle has a barrel or barrels of less than 16 inches in length. A weapon made from a rifle is also a firearm subject to the NFA if the weapon as modified has an overall length of less than 26 inches or a barrel or barrels of less than 16 inches in length

ATF.Gov

AR-15 pistols aren’t that far from SBRs in reality. They are legal in some places where SBRs aren’t, but they suffer most of the same practical difficulties as an SBR, plus one more: Since it’s legally a pistol, it’s technically illegal for it to have a rifle stock or vertical grip, which SBRs can have.

You’re supposed to shoot it one-handed, and the buffer tube is just that – a tube that sticks awkwardly out the back. However, there is a bit of help available in the form of a “brace” that attaches to your buffer tube and straps to your arm. BUT! This has recently seen some change and we urge you to read the next section!

NOTE: At the beginning of 2023, the ATF changed its position regarding “stabilizing braces” on pistols. As of the date of this article update, 99% of pistols with a stabilizing brace will be deemed short barreled rifles, or SBRs by this revised rule. There is an amnesty period (ends May 31st, 2023) to remove (the brace), destroy, turn in, or register your pistol which has a stabilizing brace. As a result of ever-evolving legislation happening “time-now”, if you’d like the most updated info please Follow Current ATF Regulation(s) Updates HERE.

If you own a pistol with a stabilizing brace a majority of the gun community seems to agree that removing it for the time being is the best course of action. Possessing a brace itself is not illegal. A brace attached to a pistol would be. For more information on this rule follow this link.

In case you were wondering how much speed you lose with these super-short barrels, a 7″ barrel will generally get you muzzle velocities in the 2200-2500 fps range, which is about 30% less that a 20″ barrel. A 10″ barrel will usually produce velocities of 2500-2800 fps. Both will produce a really exciting muzzle flash.

To sum up barrel length: For most people, it’s a 14.5″ (+1.5″) or 16″ barrel for easier handling in close quarters, or an 18″ or 20″ barrel for greater range and muzzle velocity. In case that choice seems a little too easy, there’s one more thing to consider.

AR-15 Gas Systems

You remember the gas port and tube that causes the bolt to cycle. These parts, from the gas port drilled in the barrel, through the gas block, tube, and the gas key in the bolt carrier, collectively make up the gas system. With a few (piston-driven or single-shot) exceptions that we won’t discuss today. Pretty much all ARs cycle this way.

What changes, though, is the location of the gas port along the barrel. The gas port MUST be located far enough from the muzzle that the pressure has time to kick the bolt carrier back before the bullet exits about 1/4000th of a second later. That demands that the gas port be a certain size, and a certain distance from the muzzle — which actually varies, because pressures change as you go further from the chamber.

So shorter barrels need a shorter gas tube, and with the gas port closer to the chamber, the pressures are higher.

Not just a little higher, either. Dramatically higher.

| Gas System | Gas Port Location | Pressure (PSI) |

|---|---|---|

| Pistol | 4.7″ | 48,300 |

| Carbine | 7.8″ | 33,000 |

| Mid-Length | 9.8″ | 26,500 |

| Rifle | 13.2″ | 19,600 |

This means the shorter your gas system is, the higher the pressures it’s subjected to. The bolt and carrier are slammed harder; they work harder, and the whole system becomes far more sensitive to anything that’s not perfect.

In addition, a shorter gas system is inevitably harsher in operation, because it has to cycle in a shorter time.

The original design was the rifle-length system, and that’s what the gas system is designed around. At rifle length, an aluminum gas block is fine, which keeps weight down. But with the carbine length, the pressures are almost twice as high, and an aluminum gas block will eventually be eroded by the hot gas charges.

If you’re using a carbine length gas system, or even a mid-length, a steel gas block is recommended.

Also, as the gas systems get shorter, the size of the gas port increases, because they need to bleed off a lot of pressure in a shorter time. If the gas port is too small, the rifle will short-stroke, probably resulting in failures to feed. The port can be drilled larger, but this should be done by a qualified gunsmith, or you risk ruining the barrel.

On the other hand, if the port is too big, the rifle will be “over-gassed.” That can send the gas impulse to the bolt too early, while the shell is still locked into the chamber by pressure, and cause it to fail to eject. At the very least, an over-gassed rifle will be harsh to shoot. This can be addressed with an adjustable gas block, which lets you control how much gas bleeds through, allowing you to find the point where it cycles reliably.

For more in-depth information on the types of gas systems and which one is best for you make sure to check out this article here! In general, the longer your gas system is, the smoother and more reliably it’ll operate – though you do need a certain minimum dwell time after the bullet passes the gas port.

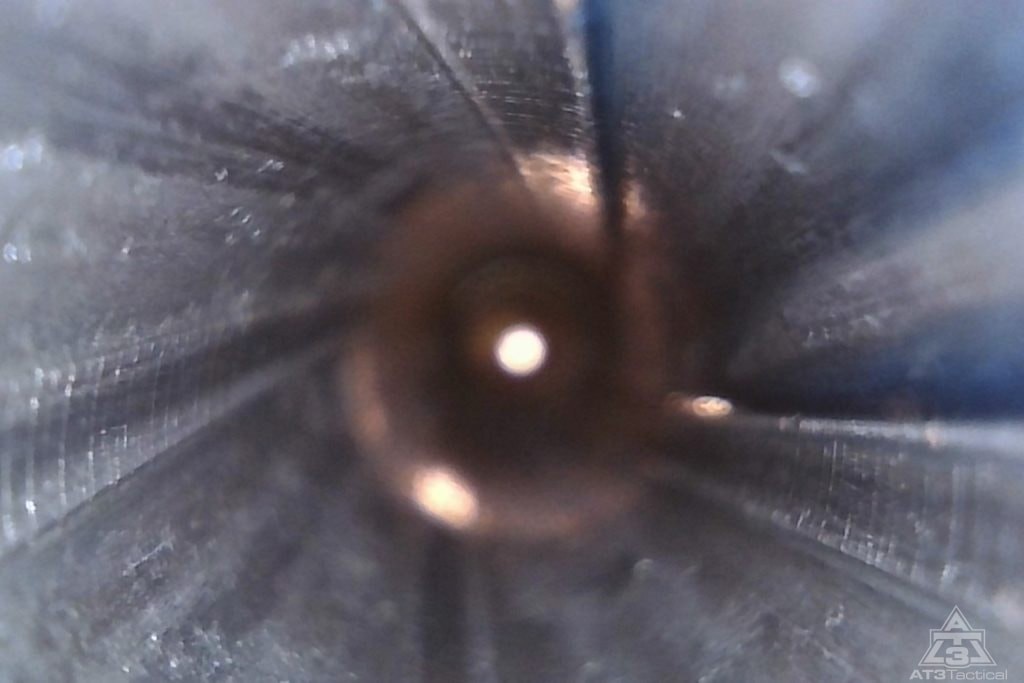

What is Barrel Rifling?

Long ago, in the early days of archery, bowmen had arrows that would regularly shoot “off” in one direction. They discovered that putting the fletching (feathers) at a slight angle caused the arrow to spin in flight, which stabilized it, constantly re-centering any irregularities in flight. Since then it’s been standard for arrows to have helical (spiral) fletching.

The same principle applies to firearms, from small handguns up to the largest artillery guns: Spinning the bullet stabilizes it in flight, and created a quantum improvement in accuracy.

What Is the Best Rifling for the Ar-15? Cut Rifling vs. Button Rifling

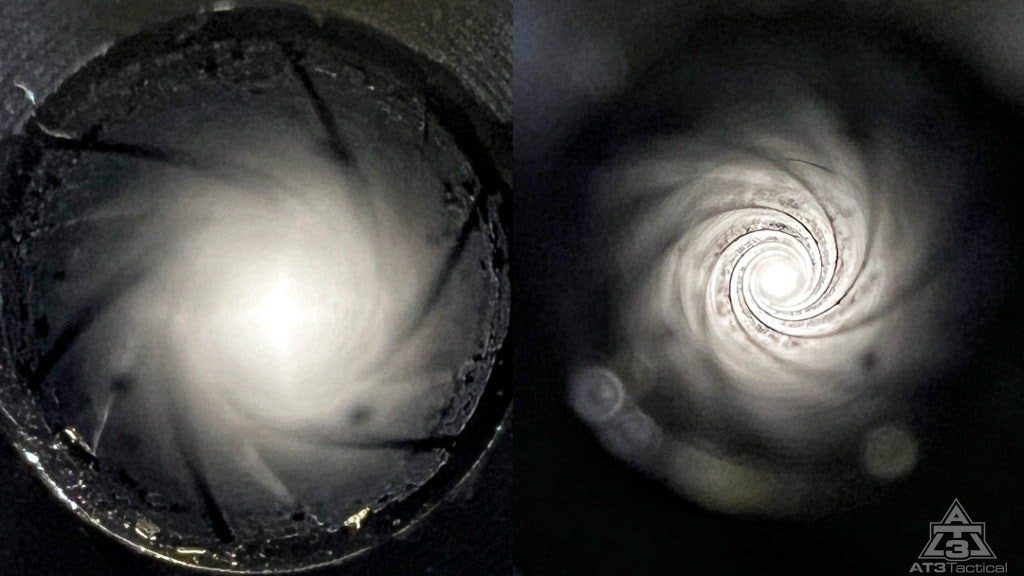

Rifling is accomplished by reshaping the inner surface of the barrel, usually with a series of spiral cuts at a very precisely controlled rate of twist. There have been two main ways of making rifling: Cut rifling and button rifling.

Cut rifling is the older process, dating back to Germany about the same time Columbus sailed to America. It is very precise and methodical, with a single cutter cutting one spiral groove at a time, one ten-thousandth of an inch deep per cut. Obviously, this takes a while — even with “modern” machines, it takes about an hour to rifle a barrel this way. (I say “modern” machines, because the last of these were built around WW2.)

World War II brought about huge changes in society and technology, and obviously, weapons technology made quantum leaps. One of the developments was the advent of “button rifling,” which can rifle a barrel in a single, 50-ton hydraulic stroke.

Button rifling doesn’t cut the grooves, like cut rifling does. The “button” on the broach head is rammed through the barrel, displacing metal by sheer force to form the grooves. This process allowed us to rapidly produce the millions of rifles needed to fight the war. On the other side, the Germans developed something quite different, which we’ll discuss a little further down.

The advent of button rifling brought speed and economy to the process, and most of the cut rifling machines were idled. Many were destroyed, but the ones that survive are treasured by custom barrel shops – and still working.

Why is that?

Even an expert would be hard-pressed to tell a button-rifled barrel from a cut-rifled barrel. The difference is there, though it’s invisible. The fifty tons of hydraulic power that form the grooves in one stroke applies tremendous stresses to the barrel steel, and those stresses can sometimes come back to haunt you – in barrels that distort when they get hot, potentially changing the point of impact. Maybe not so much that a soldier would notice it in the heat of battle, but enough that a precise target shooter might see it reflected in his groups.

For that reason, cut rifling is still used for the best, most expensive barrels — but unless you’re a top competitor, button rifling is generally good enough.

Notably, the barrel’s nominal diameter, or caliber, is measured at the lands, the high parts between the grooves. The rifling grooves are a little looser, but so is the bullet’s diameter, both about .224 inches with most ARs. As a result the lands obdurate, or cut into, the bullet’s metal jacket as it’s forced down the barrel. This involves a fair bit of mechanical resistance, creating drag, but it’s nothing 50,000 psi of pressure can’t overcome.

A .223 bullet’s cross-sectional area (Pi times radius .115″ squared) is about .039 inch; when you divide 50,000 psi by that surface area, you still have about 1950 lbs of force driving that bullet down the barrel!

(There’s another type of rifling, called polygonal rifling, which is used in many handguns, such as Glocks, but rarely used in AR barrels. While some say it’s better for various reasons, including lower mechanical drag and longer barrel life, the real-world fact is that both types produce acceptable results and are close in performance.)

Note: With the introduction of the 5th generation of Glock handguns also came the Glock “Marksman” barrel. To put it very plainly it still has polygonal rifling, it just has slightly different contours and edges to the lands and grooves.

AR-15 Twist Rate and Rate of Spin

Everything below applies to the .223/5.56 family of ammunition. Other rounds have different preferred twist rates, which will be discussed elsewhere.

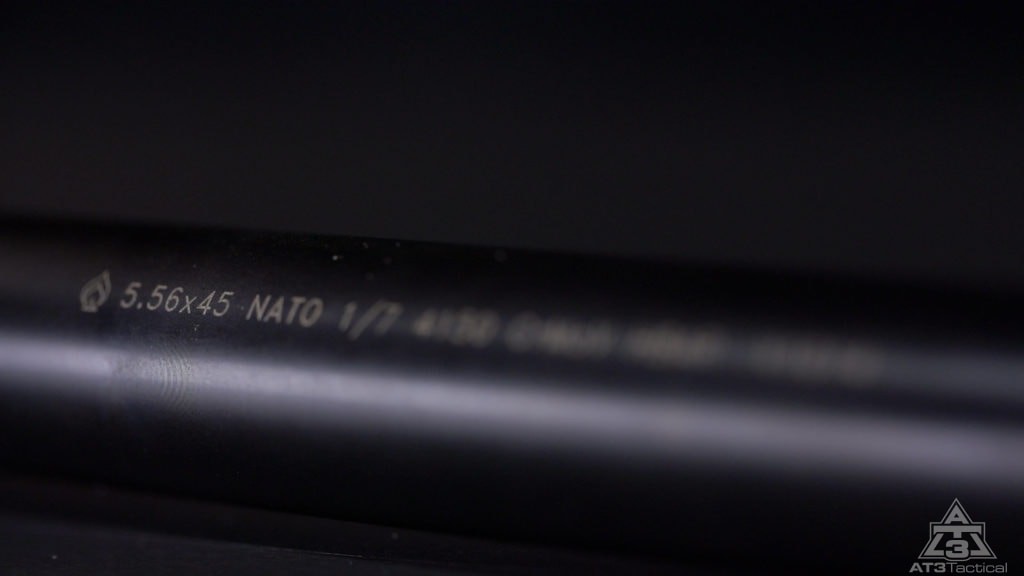

There’s a lot of debate about the rate of spin because different weights and lengths of bullets demand different spin rates. For .223 caliber and 5.56 mm, the most common rates are 1:7 or 1:9 — that is, one complete revolution in seven or nine inches of travel.

The initial production M16s were designed to shoot the 55-grain M193 round, and came with a twist rate of 1:14. This was quickly tightened to a 1:12 rate, which stabilizes a 55-grain bullet well, but really is inadequate for heavier rounds. A 1:9 twist shoots 55-grain rounds well, too, and allows ammo up to about 70 or 77 grains, depending on who you ask.

For heavier or longer bullets, above 90 grains, a faster twist rate is recommended, usually 1:7. That’s what the US military chose for the M16A2, in the 1980s, when they switched to the 62-grain M855 round, and it remains the rate of choice for the shorter-barreled M4s as well.

You might have noticed that the 1:9 twist was good up to about 77 grains, which is the heaviest most people will shoot. The military’s choice of 1:7 was dictated by the need to (sometimes) shoot the heavy M856 tracer round, which most civilians don’t really need.

“But,” you may ask, “since you can also shoot the lighter rounds with 1:7, why aren’t all AR barrels rifled at that rate?”

One answer is that some statistics indicate the 1:9 rifling stabilizes lighter bullets better than the faster rates, producing better accuracy. In addition, the physics involved point out that the energy it takes to spin the bullet is a little energy taken from the muzzle velocity, as the lands that contact the bullet have a measurable drag.

Then there’s barrel life: The faster you spin your projectile, the more energy the lands impart to the bullet, the faster they wear.

Muzzle velocity affects stabilization as well – a 1:7 SBR with a 10.5″ barrel might stabilize a 55- or 62-grain round well at about 2600 fps, but an 18- or 20-inch 1:7, shooting the same load at 3200 fps, might prove surprisingly less accurate. This is because the same twist rate, when shooting at a muzzle velocity of about 26 percent more, will spin the bullet 26% faster. Some experts would call that “over-stabilized,” while others say over-stabilization is a myth; we won’t address that question here.

Some people like a 1:8 twist rate as a compromise, which should be better for light bullets but good stabilizing projectiles up to 77 grains in weight.

The following about bullet performance is based on the military M855 round and is fairly irrelevant to someone who shoots only paper targets, but: A bullet flying from a 1:12 twist barrel (that’s one revolution per foot, obviously) at 3000 fps is spinning at a rate of 180,000 rpm. Increase the twist, and the spin rates can increase to the neighborhood of 300,000 rpm.

At this speed, the forces acting on the bullet are almost sufficient to tear it apart in flight — but not quite. That metal jacket, already obturated by the rifling, is just barely holding it all together. When the bullet hits tissue with impact speeds above about 2400 fps (remember, aerodynamic drag slows it as it flies) first it penetrates, then tends to yaw (tumble toward a butt-first orientation) because its center of mass is toward the back. As it does, the back half of the bullet typically fragments.

This is important if you’re shooting living targets, e.g., hunting because the fragments, combined with hydrostatic shock, tend to produce a much larger and more potentially lethal wound cavity than a bullet that stays in one piece. The relevance to rifling twist is that usually only a very rapidly spinning bullet – say, over 250,000 rpm – will fragment like that. A 1:12 twist won’t produce that effect, but the M855 round was developed for use with the M16A2 and its 1:7 twist barrel.

Realistically, unless you KNOW you’ll be shooting heavier rounds, you’ll probably be fine with 1:9. If you expect to shoot heavy rounds, get 1:8 or 1:7. If you’ll shoot nothing heavier than 55 grains, you might want 1:12 to maximize barrel life.

What AR Barrel Length Should You Choose?

It’s the easy answer for us but it is the truest answer. The “best one” will be different for everyone. Some folks may not be big into hunting but want a gun for home defense. Some may want to target shoot and a longer heavier option may be more likable. Combine the features you need and discard the rest.

Related Articles:

- AR-15 BARRELS – INTRO, FUNDAMENTALS, AND MANUFACTURING OF AR-15 BARRELS (PART 1)

- AR 15 BARRELS (PART TWO) – AR BARREL LENGTH (2025 UPDATE)…This Article

- AR-15 BARRELS: CALIBER, CHAMBER, & THE BEST STEEL TYPE FOR YOUR AR BARREL (PART 3)

- AR15 BARRELS: PROFILES, FLUTING, AND DIMPLING (PART 4)

- AR-15 BARRELS – SURFACE TREATMENTS & MUZZLE TYPES (PART 5)

FAQs

There is no set amount and many things factor into it such as the barrel length and type of ammunition used. It is usually agreed upon that most 5.56 barrels will be worn out by the 15,000 to 20,000-round mark.

The twist rate is the rate at which a bullet rotates fully in a given amount of barrel length. The ratio works like so: if a bullet makes one complete rotation in 8 inches then the twist rate is 1:8. Twist rates, regardless of the chambering, are subject to the length of the barrel and of ammunition choices. All bullet weights will stabilize in flight with one twist rate over another.

On average, they hover around $200. They can be hundreds of dollars more than that and may come with extras such as a gas block and tube, but a quality-made stand-alone barrel will cost around $200.

One Last Tip

If there’s anyone that knows the AR-15 platform, it’s the US military. As a special offer for our readers, you can get the Official US Army Manual for AR-15/M4/M16 right now – for free. Click here to snag a copy.

Wanting to build a 22 ar, looking at your article, what barrel, and twist would recommend

Hi Rick,

What will the intended purpose of your rifle be? Hunting, defense, trigger time toy?

Great information, very much enjoyed reading this.

John 14:6

Very informative article. Best explanation that I have seen so far and easy to read. I have a 7.5” barrel…..would it be best to add a compensator to reduce the pressure being cycled through?

Nice article! Thanks

One question can I put a 12 and a half inch barrel on top of an AR-15 pistol lower.

Is it legal to replace an 8 inch barrel with an 16 inch barrel on an AR 556 pistol. How long can the barrel be.

Will a longer gas system give you more velocity? I imagine that an 18 inch barrel with a mid length gas system will be slower by some amount because the bleed off starts sooner than a rifle length gas system. Practically, what difference in velocity does it make?

Very, Very good articles. I do have a question. I have two barrels. One with a gas port.070,the other is.085.would I need a adjustable gas block on the.085 for a 16 inch barrel?Thanks

Truly remarkable…

I am very curious about fleet yaw at close range vis-a-vis length+velocity as well as twist+land/groove effects. Such as a 5 Land/Groove barrel (said to relieve stress on the jacket versus symmetrical 4 or 6 land) and whether or not Progressive twist or smooth edged Lands produce more precision and less jacket distortion

This was a very well written article, as well as very informative. While I myself knew the majority of this information from having built AR rifles in the past, it is very encouraging to read a post such as this that has good information and a little bit of humor thrown in as well. Thank you for the knowledge!

Great reading … I’m building a system and already order the barrel few days ago. Learn a lot….. I was wondering if I should use a mid length gas system on my 16 in 1/7 twist barrel…r carbine… Its coming with carbine … ?… And I was wondering if pressure builds as gas is shorten . Which buffer should I go …heavy ..are ex-heavy…I’ll be shooting heavier rounds deer and big game .. won’t shoot less then 65 grin I’m guessing . Any Intel would be very greatful. And much appreciated… Thanks you

Your articles are great!

Really well written and intelligent. Thank you.

Very easy to understand, and very helpful! I’ll be passing this on. Thanks!!

Great reference reading for those those who want to understand how their ARs should work. I googled the question “how far should my gas block be along an AR barrel, and it lead me here. Kudos

Thanks for the article. I enjoyed reading it. It was written well because although it’s easy to get too technical it was kept simple enough to where I didn’t get lost. I’ll be looking forward to reading others!

Thanks for all the great article’s regarding the AR15! Each one is simple enough to understand and breaking into 4-5 segments makes it an easy read!

Keep them coming,

Brilliant literary discussion. I throughly enjoyed. Makes everything easier to understand.

Thank you,

William Nunnally